(Originally submitted for Museums and the Web 2015. Co-authored with Desi Gonzalez and Kurt Fendt.)

Abstract

How can we engineer the discovery of art? HyperStudio, MIT’s digital humanities laboratory, has been tackling this question through the development of Artbot, a mobile website that encourages meaningful, sustained relationships to art museums in the Boston area. Artbot combines two strategies to enable users to discover cultural happenings in the city: a serendipitous approach that allows users to explore via linkages between art events, and a recommendation system that suggests events based on a user’s interests.

Using Artbot as its primary case study, this paper will examine the design and building of art discovery systems. First, it will survey other examples of art recommendation and discovery systems, such as Magic Tate Ball, Serendip-o-matic, Artsy, and the Powerhouse’s OPAC 2.0 collection project. Then we will discuss the front-end design and back-end technologies behind Artbot’s discovery engine and consider how other cultural institutions can implement these approaches.

1. Introduction

At HyperStudio, MIT’s digital humanities center, we research, conceptualize, and develop projects in support of scholarship and education in the humanities. Each project starts with a clearly defined scholarly and/or educational need, often in partnership with MIT faculty and local institutions. We then expand on existing digital humanities research to develop tools that can be applied to other humanities fields.

In the fall of 2013, HyperStudio began work on Artbot (artbotapp.com), a mobile website that allows users to discover art in the Boston area. We wanted to go beyond a listings website or a tourist guide. Instead, Artbot aims to create deeper connections to art through personalization and by unearthing hidden gems within Boston’s cultural landscape. As such, we targeted an audience of Boston-area residents who are interested in art but may not be aware of all of the city’s cultural happenings; we especially aim to reach Boston’s semi-transient student and researcher population. Artbot aims to accomplish three goals:

- To encourage a meaningful and sustained relationship to art

- To do so by getting users physically in front of works of art

- To reveal the rich connections among holdings and activities at cultural institutions in Boston

During Artbot’s ideation process, one advisor likened Boston as a whole to a museum: from attending lectures at Tufts University to concerts at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, an individual could enjoy a wealth of educational and cultural experiences within the city. But many people don’t know how to find out about new happenings in Boston’s art scene, and while they can turn to email digests and newspapers listings, few tools provide personalized and playful recommendations for arts and culture.

We endeavored to accomplish these goals by building a tool that addressed a research question: How can we engineer the discovery of art? Beyond this core question, what audience would be most interested in such a tool, and how can we best reach them? Finally, how can we balance a smart, engaging, scalable, and sustainable discovery system with time and budget limitations?

This paper examines the research and process of developing a discovery system for visual art events and exhibitions in the Boston area. First, we review the challenges to algorithmic recommendation and discovery in the cultural sector, assessing existing recommendation models. For Artbot, we opted for two modes of discovery: a serendipitous and playful approach that allows users to explore via linkages between art events, and a recommendation system that suggests events based on a user’s interests. The following section addresses our process and approach while designing and developing Artbot. Next, we describe the app’s interface design and the ways it reflects Artbot’s two modes of discovery. We then outline the back-end system, which is built around a suite of modular components, services, and open-source tools; it combines Web scraping and natural-language processing tools to semi-automate the data sourcing and tagging process. After outlining our next steps, we conclude by considering what other cultural institutions might learn from this project.

2. Cultural recommendation and discovery

Recommendation and discovery systems are plentiful, and many of us use them on a daily basis. When a user opens Netflix, it might recommend that she watch The IT Crowd and All About Eve because she previously binged on 30 Rock and tends to watch classic films with strong female heroines. For another individual, an app called Zite bookmarks news articles based on topics he’s chosen to follow, such as “museums,” “digital humanities,” and “politics.” And for yet another person, Amazon.com might recommend a Columbia fleece vest because she was browsing a Patagonia jacket.

Cultural institutions can employ recommendation systems, but for different ends than their for-profit counterparts. For museums, cultural organizations, and university-affiliated research groups like HyperStudio, our goals are more intangible: rather than increasing the bottom line, we aim to increase engagement with culture at large. In The Participatory Museum (2010), Nina Simon advocates for personalized recommendation systems as a way to frame “the entry experience in a way that makes visitors feel valued,” provide “opportunities to deepen and satisfy their pre-existing interests,” and give “people confidence to branch out to challenging and unfamiliar opportunities.” Barry Schwartz (2008) discusses how recommendation in the cultural space, unlike the commercial space, is not an either-or situation. You can choose both the Philip Roth and the Steven King novels to read on a cross-country flight, he explains. In fact, diversity in cultural consumption might lead to further interest in culture: “Perhaps because culture is an experienced good, participating in cultural events may whet the appetite for more participation. Doing culture may stimulate the demand for more culture” (Schwartz, 2008). Richard A. Peterson and Gabriel Rossman (2008) call an interest in a variety of culture—from the highbrow to popular culture—“omnivorousness” and argue that omnivorousness might be an increasingly important factor in predicting whether a person will participate in cultural events than his or her “brow level of taste.”

But while diversity of choice is a good thing—and something we certainly hope to emphasize in Artbot—too much choice can be a bad thing. Schwartz talks of the problem of “choice overload” and the “paradox of choice,” in which a surplus of cultural options can lead to people participating less. He suggests that having too much choice can result in dissatisfaction with a final decision, or a feeling of paralysis in the face of so many options; often, people will choose the same things that they are used to or “choose not to choose at all.” In a focus group we conducted during the conceptualization phase of Artbot, participants expressed frustration with massive lists of cultural options. Rather than sifting through comprehensive event feeds or digests, they tended to find out about events through their social networks or directed emails. Schwartz comes to a similar conclusion: he advocates for cultural institutions to focus “more on filtering diversity than creating it.” In other words, now that the Internet allows access to so many artworks, films, books, and music, how can we build tools to help users make sense of such a wealth of culture?

These are considerations we have kept in mind during the development of Artbot. We hope to expand users’ cultural purview by suggesting hidden gems they may not have known they were interested in; at the same time, we want users to feel like the cultural events and exhibitions recommended to them align with their own interests and sense of identity.

In designing Artbot’s discovery engine, we looked to existing models of cultural recommendation systems. Recommendation systems can be divided into two main approaches: collaborative filtering and content-based filtering. Collaborative systems take on a social approach, giving recommendations based on users’ behavior. Amazon, for example, employs item-to-item collaborative filtering, showing that people who buy product X also bought product Y. Netflix recommends movies and TV shows that you might like based on other users who have similar viewing habits. In the museum realm, the Powerhouse Museum’s OPAC2.0 collection search interface integrates what Seb Chan (2007) has called “frictionless serendipity.” OPAC2.0 provides users suggestions for collection objects according to the behavior of site visitors; as Chan explains, a search “for ‘minton’ currently gets suggestions for other searches of ‘mintons’, ‘bone china’, ‘british’, ‘porcelain’ and ‘peacock’, based on the terms other searchers of the term ‘minton’ have used and the objects they have viewed.”

One of the drawbacks of collaborative filtering, however, is that it can limit rather than expand a user’s purview. Early utopian language surrounding collaborative filtering championed its power to break down rigid demographic groups, but as Nick Seaver (2012) points out, collaborative filtering merely redraws borders based on consumer taste (which often fall along traditional demographic lines), and its dynamic, shifting nature can make it seem invisible and immune to scrutiny. Eli Pariser (2011) coined the term “filter bubble” to describe the phenomenon that occurs when an algorithm, guessing what a user might want, isolates said user from content that might differ from his or her viewpoints. In order to combat such filter bubbles, Ethan Zuckerman (2013) advocates for the building of digital tools that infuse serendipity and a diversity of voices.

Collaborative filtering also suffers from the “cold start” problem (Schein et al., 2002): a system doesn’t know how to evaluate items that no user has rated yet. It thus requires a strong user base at the outset in order to be effective—no recommender system uses collaborative filtering exclusively—and only gets better with more and more users. While this approach works for Netflix or Amazon, we opted against implementing collaborative filtering at an early stage for the reasons outlined above.

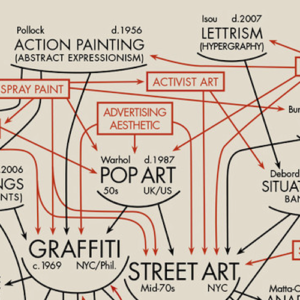

Content-based systems look to the properties of the items themselves, rather than the users, for recommendation signals. The Powerhouse Museum’s OPAC2.0 also incorporates content-based recommendation strategies, taking advantage of the object and subject taxonomies built into museum’s collection management system while also allowing users to add tags to objects in the collection. Trill (www.trill.me), a Boston-based service for discovering music and performance events, allows users to explore via genre tags. Trill also suggests curated picks from local music and performance experts. Artsy’s “Art Genome Project” is a more nuanced tagging system; artworks are tagged by “genes” that are assigned priority on a scale from 0 to 100. Like collaborative discovery tools, tag-based recommendation systems have disadvantages. Whether tags are user generated or curated by a selected team, generating and maintaining a taxonomy can be time intensive. Additionally, tags are only as good as their taggers, often leading to rigid classifications that don’t allow for happy accidents in the discovery process.

Serendip-o-matic and Magic Tate Ball are two content-based recommendation projects that hope to infuse serendipity into the discovery process. Serendip-o-matic, a website created in August 2013 and geared toward scholarly researchers, asks users to input a text; the tool identifies key words within the text and yields images from online humanities collections. The results can serve as inspiration for a new research project or unexpected primary sources that can enliven a project. Magic Tate Ball is a mobile app that provides a fun way to discover artworks within the Tate’s collection. Based on factors such as GPS location, time of day, current weather conditions, and ambient noise levels, the “eight ball” yields one artwork, providing an explanation as to why the object was selected and additional educational content.

In developing Artbot, we wanted to emulate Serendip-o-matic and Magic Tate Ball’s sense of discovery and fun. We initially considered many search strategies: most popular events, events happening or exhibitions closing soonest, curated lists, and so on. Ultimately, we opted for a content-based approach that combines two main modes of discovery: personalized recommendations based on favorites and user interests, and serendipitous connections between events, based on automatically generated tags.

3. Process

HyperStudio is a research group within an academic unit, consisting of graduate research assistants, technical, and academic staff. Besides Digital Humanities research and education, we develop a variety of grant-funded projects. As such, our application needed to be buildable and sustainable within this framework. The project’s small team and limited time frame informed both the scope and the process of building Artbot, as we aimed to balance research interests with practical concerns.

We began the process with extensive background research into existing museum, event recommendation, and mobile discovery apps, as well as conversations and focus groups with potential target users in the MIT community. These confirmed that people felt overwhelmed by the plethora of events in Boston and wanted help in sorting through them to find interesting happenings.

With this less-is-more approach in mind, we started small, sourcing our data from a handful of museums in Boston rather than expanding too quickly to other venues or types of events. We also decided to hone in on event and exhibition data, rather than collections, in part because of access and rights issues; museum collection data is often difficult to access, while event information is freely available on the Web. By starting small, we were able to keep our focus on providing rich and nuanced recommendations rather than worrying about quantity and scale. The decision to work with events and exhibitions also helped to focus our app’s goals: rather than educating users from afar, the app would aim to encourage users to attend the museums themselves.

After the initial research phase, we began designing and prototyping Artbot in spring 2014. We opted for a mobile website, as we wanted to design for a mobile audience without adding the technical demands and overhead of a native mobile application. This allows the app to work responsively on any device, which is particularly helpful at our stage for user testing. Future versions of Artbot could also build on this backbone for new, mobile-specific features and integration with app stores.

Figure 1: early paper prototype

We developed the core features of Artbot between April and October 2014. In the process, we extensively leveraged third-party and open-source technologies and services. We also supplemented in-house development with contract work from outside consultants, working primarily in a series of intensive sprints. We collaborated with design firm Clearbold (clearbold.com) on the front-end execution and user experience, and with the consulting firm Thoughtbot (thoughtbot.com) on aspects ranging from visual design to application programming interface (API) structure.

4. Front-end design

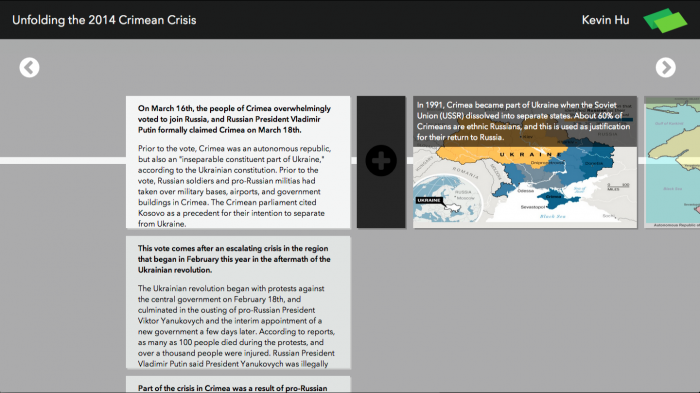

Artbot’s front-end design reflects the two modes of discovery outlined above. The landing page, also called the “Discover” page, reflects the personalized-recommendation aspect of the application. On the top two-thirds of the screen, a signed-in user sees one event or exhibition at a time based on his or her preferences. The user can swipe left or right to browse up to ten other recommendations. The decision to show only one event at a time was influenced by the Magic Tate Ball app: by displaying only one recommendation at a time, that recommendation becomes all the more special to the user and avoids overloading the user with too many options. On the bottom third of the same screen, a user can access the events and exhibitions they’ve saved via the “My Favorites” carousel.

Figure 2: the Discover page

Event and exhibition pages are designed to reveal the serendipitous connections between events. The bottom carousel—mirroring the “My Favorites” navigation of the “Discover” page—recommends other events and exhibitions based on related tags. Users can tap on the “refresh” icon to load another tag related to the event on view. Pairing specific event information with other recommendations emphasizes the connections between events across the Boston area, visualized on a single screen.

Figure 3: a sample event page

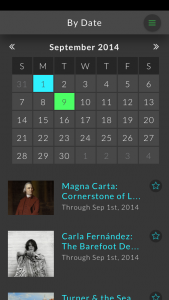

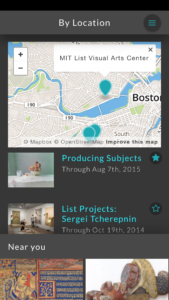

While personalized recommendations and serendipitous connections are the primary modes of discovery on Artbot, we recognize that users are also interested in finding happenings that are convenient for their busy schedules. With this in mind, we also allow users to filter events by date and by location. However, we purposefully excluded search functionality from the app. By limiting its design to only a few modes of discovery, we hope to develop a simple but elegant tool that prioritizes serendipitous discovery above all.

Figure 4: “By Date” and “By Location” pages

5. Technology pipeline

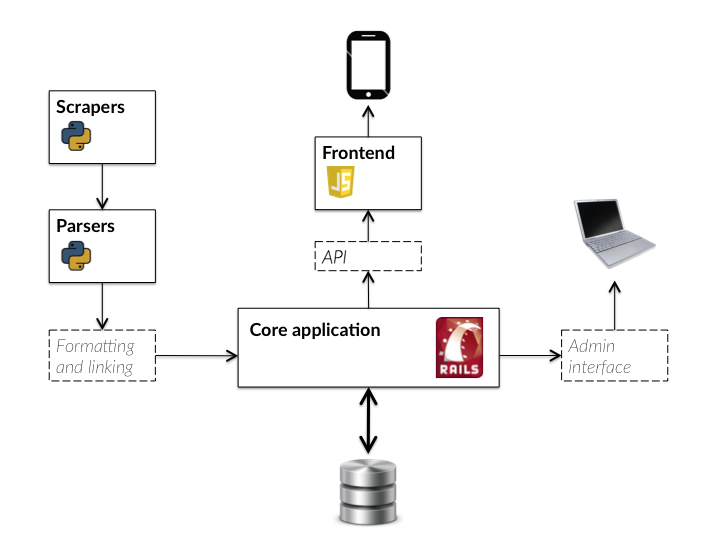

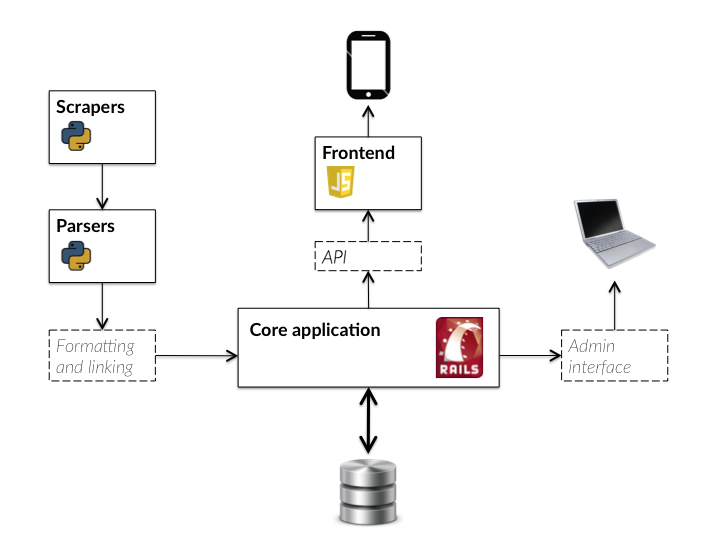

The back end of Artbot’s technology stack is designed to support a unique and nuanced recommendation engine that can complement and reinforce these playful, serendipitous elements of user discovery. We also endeavor to make Artbot a suite of modular, easily customizable components in order to further scale and develop particular elements, as well as lending itself to future reuse.

Artbot’s back-end ecosystem consists of three major components that will be described in the following sections:

- A series of Web scrapers to obtain the event data

- A Web-based natural language parser and named entity recognition service

- A back-end API with user and admin management capabilities

Figure 5: diagram of Artbot’s applications and features

- Scrapers

One of the biggest challenges in building and maintaining an event recommendation application is the sourcing of event data. Events come in many forms and from many sources, so finding an optimal approach for adding and classifying every event is a particular challenge. Some event applications ask partners (such as museums, galleries, or marketers) to enter data into an online form; others rely on staff or interns who actively scour the Web and manually enter data, while still others crowdsource submissions from the public.

Artbot’s event data comes directly from museum websites via scraping. A scraper is an automated script that fetches a Web page in order to extract and store certain data from it. For instance, the Web page for the Museum of Fine Arts’ Goya: Order and Disorder exhibition (mfa.org/exhibitions/goya) contains a plethora of useful metadata: start and end dates, gallery location, images, price, and most importantly for Artbot, a four-hundred-word description of the exhibition complete with associated artists, movements, themes, and locations.

The scraper approach allows Artbot to use a “pull” model that automatically grabs event data, rather than a “push” model in which administrators manually find and enter event information. The primary benefit of scrapers lies in its flexibility; we do not require museums to directly supply data in a certain format, repeating work that they might do elsewhere. Scrapers also obviate the need for our staff to scour museum websites for new or updated events, as the scraping scripts do so for us.

We have built scrapers for seven of the eight museums in our system. While every museum structures its website differently, each of these museums follows a certain formula for event pages and listings. The museum homepage tends to lead to an event or exhibition index page, which our scrapers are able to locate and fetch in order to collect a full and updated event listing. The conventions and patterns in museum websites also allow us to add most conventional museum websites efficiently, with just a few lines of code. The scraper then visits each event page in the listing and gathers the exhibition’s URL, name, dates, location, image, and full-text description. It yields a list of these events in the JSON data format for storage in a database.

We currently run each of the seven scrapers once a day to check for new and updated events. Any changes are handled automatically by cross-referencing the exhibition’s URL with the corresponding URL in our system. If the event’s metadata (such as its dates or description) has changed, it will automatically update the event with the new data and alert any admins about the change.

The scraper approach, while successful and useful for our purposes, has certain drawbacks and limitations. First, a website must be well structured in order to retrieve the data, which makes the approach better suited to institutions with a well-developed Web presence. Moreover, when a museum redesigns its website, the scraper needs to be rewritten. Second, the approach necessitates a “closed” ecosystem of venues, with a bespoke scraper for each venue. Still, we see this method as more consistent and sustainable than manually adding and maintaining all of the venue’s events.

Although the scraping approach does not lend itself as well to smaller, more ad hoc events with less of a Web presence, it can easily be used in tandem with other sourcing methods, such as manually entering event data into the database. For our purposes, the scrapers have proven helpful for maintaining a small but sustainable set of data with the potential for rich interconnections.

- Parsers

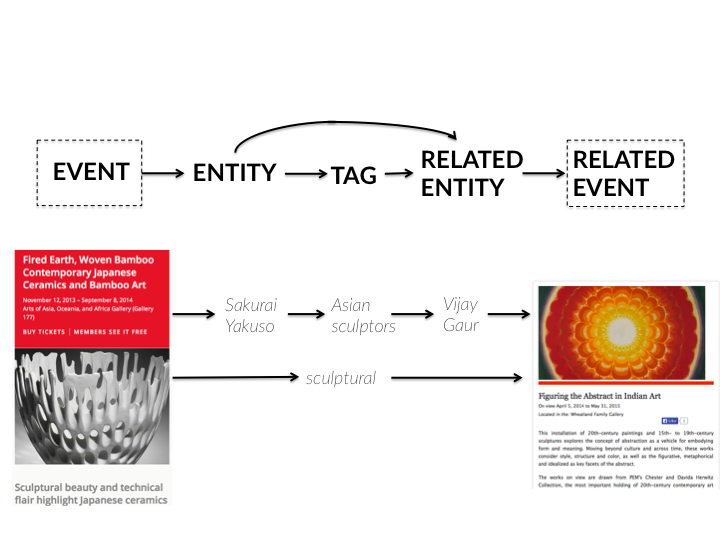

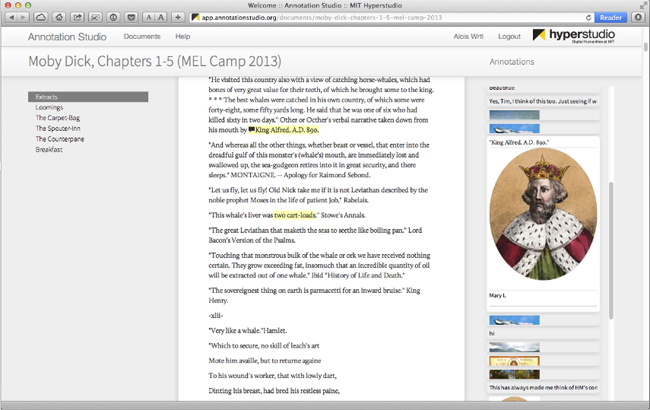

Most museum event pages include a description of the event to entice users to attend. These descriptions are replete with rich and useful information, such as artists, movements, mediums, and geographic locations that make up a web of connections and influences. In order to tie these influences to collections, events, and exhibitions at other museums, we utilize a suite of third-party natural-language processing tools, which help with tasks like named entity recognition and entity linking. Named entity recognition (NER) is a process that identifies and classifies text elements, such as the names of people, locations, and organizations. Entity linking takes these names and connects them to a broader knowledge base, such as Wikipedia. Together, these services, which we call “parsers,” extract proper names and broader themes from a given text (such as an event description), allowing for automated categorization, classification, and linking of events and their contents.

The resulting application, written in Python’s Flask framework, allows a user to supply any text (i.e., a museum event description) to the suite of parsers. The parsers will then return a list of entities (proper names) and tags (descriptions and themes) that are associated with the text. We have so far implemented four different services in tandem: the Stanford Named Entity Recognizer, DBpedia, OpenCalais, and Zemanta.

We found that the Stanford Named Entity Recognizer (nlp.stanford.edu/software/CRF-NER.shtml) was the most effective of the four services at identifying the presence of entities—people, places, and organizations—in event descriptions. However, unlike the other services, Stanford does not automatically link or disambiguate these entities. To compensate, we rely on linked-data service DBpedia (wiki.dbpedia.org) to match the recognized text to a specific entity with contextual meaning. So for instance, if the string “Sol LeWitt” is in a given event description, the Stanford NER will recognize that Sol LeWitt is a person, and DBpedia will link it to Sol LeWitt’s Wikipedia page, which leads in turn to additional insight (e.g., that Sol LeWitt is a Conceptual artist, an American, and so on).

While the Stanford NER is effective at finding the proper names in a given text, it is not built to locate or infer broader topics and themes. To shore up this aspect, we rely on third-party API services OpenCalais (opencalais.com) and Zemanta (zemanta.com). Like DBpedia, these services find linked entities and tags in free text. They are primarily targeted towards news and blog classification, so they sometimes provide superfluous or irrelevant tags to art events; however, since we combine multiple linked-data services, we are able to triangulate between these tags in order to vet or confirm their accuracy.

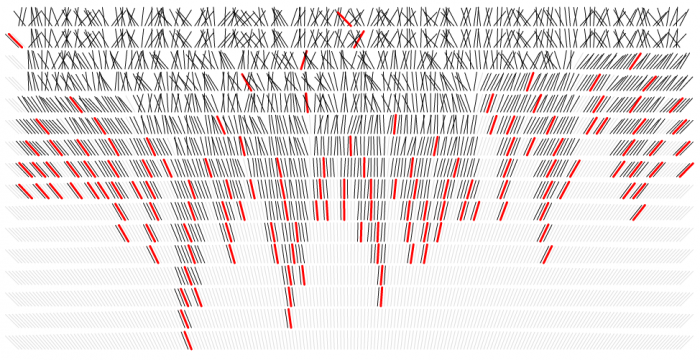

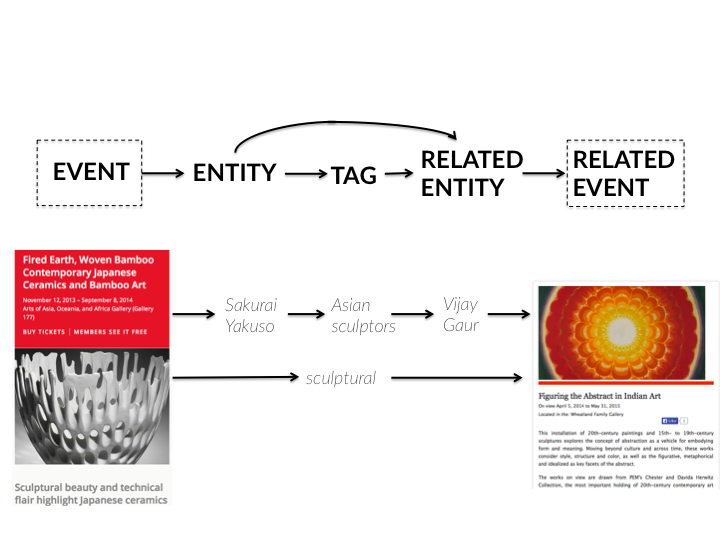

Figure 6: diagram of the data ingestion and tagging process, from event page to database

Our integrated approach, combining multiple services in a single Web application, allows us to balance the strengths and weaknesses of each service. It also allows us to easily add new parsers to the same application, rather than building different applications for each service. For instance, certain Getty Vocabularies (getty.edu/research/tools/vocabularies), like the Union List of Artist Names, would be a promising addition for deeper dives into the connections between artists and art movements. The open-source Stanford NER is also highly customizable, allowing for the long-term possibility of creating a custom entity recognizer built specifically for museum exhibits and descriptions.

- Core application and API

After the scraping and parsing process, the event data is sent to Artbot’s core back-end and API, which is written in the Ruby on Rails framework. Along with housing the database and its corresponding data models, the core application contains some of the pre-ingestion data management required to format the data for use, such as a date parser and an entity linker. It also provides API endpoints for use by a front-end presentation system, as well as admin management and email features.

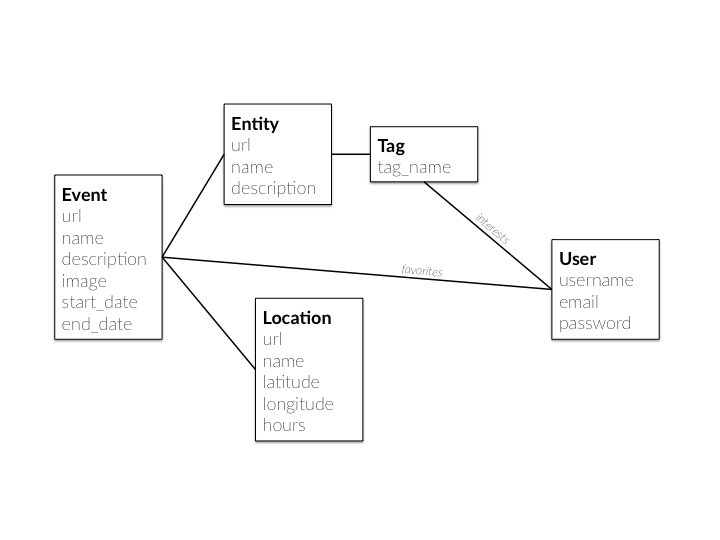

The entity linker manages the parsers’ entities and tags, and makes smart and dynamic connections between these entities for future use. Due to the often-noisy data coming from the parsers, the entity linker blocks any tags except those matching a given whitelist of regular expressions. Terms like “artist” and “sculpture” will be recognized as relevant tags and therefore applied, while less-relevant tags like “banking” or “philanthropist” are thrown out. These regular expressions also allow for tagging on dynamic contexts, such as “movement,” “medium,” or “era”; therefore, the system will understand that an artist who is tagged as “baroque” and “Spanish” is being tagged according to an era and a location, respectively. This allows for more nuanced recommendations that incorporate context and source variety in the selection algorithms.

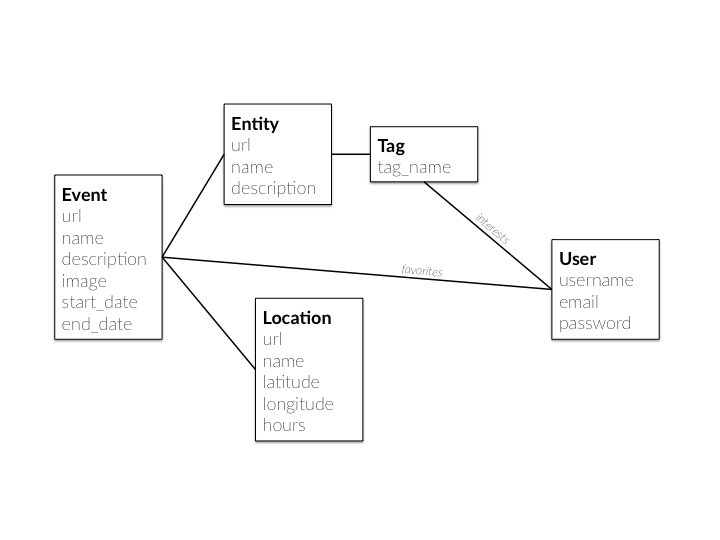

Figure 7: diagram of the database schema, demonstrating how events connect to other events and users

This approach is more sustainable than directly tagging events themselves; by instead tagging the entities associated with the event, the system learns how to tag future events containing that entity. For instance, if the artist Marina Abramovic is tagged with “performance art,” any future event mentioning Abramovic will be automatically tagged as such, rather than requiring new tags on a per-event basis.

- API (Application Programming Interface)

The application programming interface (API) allows the separate parts of Artbot talk to each other by sending and receiving dynamic and customizable data via JSON, a lightweight data format that allows for easy integration with any front-end interface. The API has built-in functionality for event and location search and filtering—such as by date, location, user interest, and event relevancy—as well as user authentication and management.

The core API endpoints correspond to Artbot’s two main approaches to discovery: personal recommendations (used on the user “Discover” page), and serendipitous cross-event connections (used on the event and venue pages).

The “Discover” API takes into account a user’s interests (gathered when the user signs up, or when they go to their “My Interests” page), as well as a user’s favorited events. The algorithm first searches for all current events tagged with a user’s interests, as well as all the tags associated with a user’s favorite events. It then withholds any events that have already been favorited by the user. Finally, it orders the events based on heuristics such as tag quantity, event location, and contextual variety. If no events are found, or if the user is not signed in, it defaults to ordering by date, recommending events and exhibitions that close soon.

The cross-event API, which populates the bottom carousel of the event page, looks for signals in the properties of the events themselves, rather than the preferences of the user requesting the event. It utilizes a mix of approaches to determine relevancy and ultimately display and sort items for the user. This includes direct entity relationships (such as a certain artist appearing in two different events), as well as tags associated with these entities (such as an art movement that is associated with two artists mentioned in different events).

Figure 8: diagram of the query process. Events are linked via both entities and tags.

To support the need for users to find events by date and location, the API can also return a list of events in a given year, month, or specific day, or events occurring within a given radius of a latitude and longitude.

The scrapers, parsers, and API are built to minimize the need for human maintenance and interference, but Artbot is built on the assumption that human curation is important to the recommendation system; the automated elements exist primarily to supplement and streamline, rather than entirely replace, the work needed to maintain it. As such, the application includes an interface for admin users to manage and connect events, entities, and locations in Artbot. One of the more notable custom functions in the Artbot admin interface allows admins to manually run the natural language parsers on a new or changed event. This gives admins the ability to manually add events without the need for a scraper, but still take advantage of the automated natural language tools.

6. Next steps

In spring 2015, we will be conducting extensive beta testing of Artbot. We hope to investigate in which situations people use Artbot, how often, how long they access the app, and how they take advantage of profile-specific functionalities such as favorites and history. We’re also hoping that user research might begin to answer our larger questions: Can a digital tool like Artbot foster sustained engagement with the arts? Can we engineer the discovery of art through content-based filtering and a dash of serendipity?

In the future, we plan to further modularize parts of the application in order to prepare them for open-source use. For example, the parser technology could be available so that cultural institutions may take advantage of automatic tagging and linking for their own projects, without having to use other parts of Artbot. An open-source Artbot could also potentially be adopted as a whole; this would allow anyone to build their own Artbot with a customized ecosystem of events and venues.

7. Conclusion

At HyperStudio, we collaborate closely with scholars, educators, and students, often building open-source tools that can be reimagined for many contexts. In developing Artbot, we are excited to build a better cultural discovery system, but we also hope the research we have conducted in the process can aid others as they build their own personalization and recommendation tools. Cultural agents, such as local arts councils or consortiums of museums, can adopt the strategies outlined above to reveal connections across institutions. Individual museums, too, can repurpose many of the same strategies to build recommendation systems within their own institutions. For example, a museum might adopt an Artbot-like approach to reveal a web of influences between artists in an exhibition. Museums can apply Artbot’s parser system—a combination of named entity recognition, natural language processing, and linked-data services—to collection objects, so long as collection objects have rich enough data/descriptions.

We hope that the Artbot case study illuminates three main takeaways that cultural organizations on a budget can apply to their own projects:

- Design for diversity, but don’t overload your user with too many options. Barry Schwartz (2008) introduces the “paradox of choice,” in which too much choice can lead to decreased participation with culture. When a user is faced with a surplus of options, he or she may be less satisfied with the ultimate decision, or may choose to not choose at all. When designing Artbot, we wanted to build a system that would surprise users with options they may not have been aware of, but we also wanted to avoid overloading them with too many choices. Our interface is designed to limit the recommendations a user sees at any one moment, while allowing him or her to dig deeper into the connections between events and exhibitions. The back-end system and data schema are built to support this, allowing for a wide variety of diverse and sometimes unconventional recommendations.

- Build a system that allows for a hybrid of automation and curation. Populating event and exhibition data and maintaining a robust tagging system tend to be time intensive. At HyperStudio, we’re a small staff working on multiple projects; when developing Artbot, we needed to devise a recommendation system that wouldn’t require staff to spend the majority of their time on the upkeep of content. By writing scrapers that retrieve event information from museum websites and running parsers to automatically categorize, classify, and link events, we were able to build a tool that does much of the leg work for us. However, the best discovery systems allow room for human curation. Artbot’s admin interface lets our team add tags manually; by associating the tags with entities rather than specific events or exhibitions, the system learns from the human curation to similarly tag future events containing those entities. A hybrid automated/curated approach affords Artbot the nuance of recommendation apps like Artsy while saving on time and staff resources.

- Utilize existing APIs and tools. Like all good software developers, we didn’t reinvent the wheel. Instead, Artbot is built on a variety of open-source frameworks, libraries, gems, and services used for Web scraping, testing, admin management, and many other features. Notably, we used four free services—the Stanford Named Entity Recognizer, DBpedia, OpenCalais, and Zemanta—as the core of our automated tagging system. By combining the four services into our recommendation system, we were able to take advantage of the strengths of each.

In our introduction, we identified Artbot’s audience as Boston locals who want to learn more about the visual arts in the area. While this remains true, we hope that Artbot will be useful beyond this community: not just to the end users, but also to designers and technologists in the cultural sector who could learn from our research, strategies, and process.

Acknowledgements

Artbot was developed as a collaboration among many individuals and groups surrounding HyperStudio, all of whom have been instrumental in Artbot’s design and implementation. Special thanks to Kurt Fendt, Jamie Folsom, Mark Reeves and Clearbold, Daniel Collins-Puro and Thoughtbot, Hannah Pang, Gabriella Horvath, Rachel Schnepper, Andy Stuhl, and the HyperStudio team.

References

Chan, S. (2007). “Tagging and Searching—Serendipity and Museum Collection Databases.” In J. Trant & D. Bearman (eds.). Museums and the Web 2007: Proceedings. Toronto: Archives & Museum Informatics. Available http://www.archimuse.com/mw2007/papers/chan/chan.html

Pariser, E. (2011). The Filter Bubble: What the Internet is Hiding From You. London: Penguin UK.

Peterson, R. A., & G. Rossman. (2008). “Changing Arts Audiences: Capitalizing on Omnivorousness.” In W. Ivey & S. J. Tepper (eds.). Engaging Art: The Next Great Transformation of America’s Cultural Life. New York: Routledge.

Schein, A. I., A. Popescul, L. H. Ungar, & D. M. Pennock. (2002). “Methods and Metrics for Cold-Start Recommendations.” Proceedings of the 25th Annual International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval SIGIR 2002). New York: Association for Computer Machinery. 253–260.

Schwartz, B. (2008). “Can There Ever Be Too Many Flowers Blooming?” In W. Ivey & S. J. Tepper (eds.). Engaging Art: The Next Great Transformation of America’s Cultural Life. New York: Routledge.

Seaver, N. (2012). “Algorithmic Recommendations and Synaptic Functions | Limn.” Limn 2, 44–47.

Simon, N. (2010). The Participatory Museum. Santa Cruz, CA: Museum 2.0.

Zuckerman, E. (2013). Rewire: Digital Cosmopolitans in the Age of Connection. New York: WW Norton & Company.

To further explore this convergence, earlier this month MIT’s

To further explore this convergence, earlier this month MIT’s  Another major difference is that, while docs can take years to create, news is inherently fast-paced. Longform works emerge between these time scales, of course, and can be crucial for bringing the public’s attention to complex story arcs; this type of storytelling helps the audience place newsworthy events in the context of larger historical phenomena. Interactive features might have form and marketing challenges, but they can play a crucial role in balancing the time scale of the news cycle.

Another major difference is that, while docs can take years to create, news is inherently fast-paced. Longform works emerge between these time scales, of course, and can be crucial for bringing the public’s attention to complex story arcs; this type of storytelling helps the audience place newsworthy events in the context of larger historical phenomena. Interactive features might have form and marketing challenges, but they can play a crucial role in balancing the time scale of the news cycle.

As might be expected, some results are more serendipitous than others. It’s also hard to know why a certain image or document was selected, which could otherwise be helpful in directing future searches. All the same, Serendip-o-matic’s playful setup and language prime the user well for making accidental discoveries.

As might be expected, some results are more serendipitous than others. It’s also hard to know why a certain image or document was selected, which could otherwise be helpful in directing future searches. All the same, Serendip-o-matic’s playful setup and language prime the user well for making accidental discoveries.

Enter

Enter  FOLD was born out of

FOLD was born out of